The True Cost of Being a “Traitor”

- Mike Lamb

- Oct 15, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 13

One week ago, more than six million of us tuned into The Celebrity Traitors (UK) – and haven’t stopped talking about it since! Starring a raft of bona fide household names – a rarity for “celebrity” editions nowadays – the opening episode delivered a feast of mind games, side-eyes, and rising paranoia as 19 hopefuls descended on the Scottish Highlands to root out the traitors among them, all in the name of charity.

And it didn’t take long for the accusations to fly. Within minutes of the first task, comedian Alan Carr was already confiding to a car full of as-yet-unordained co-stars:

Y’know who I’m suspicious of… Jonathan. Did you see how he dug his grave?

That throwaway comment perfectly captured what makes The Traitors so compelling. It’s never just about who wins; it’s about watching how people navigate uncertainty – and, in Alan’s case, start second-guessing before the real deception has even begun. Every raised eyebrow, nervous laugh, or overuse of the word “flabbergasted” becomes a clue in a social experiment that’s equal parts murder mystery and psychological endurance test.

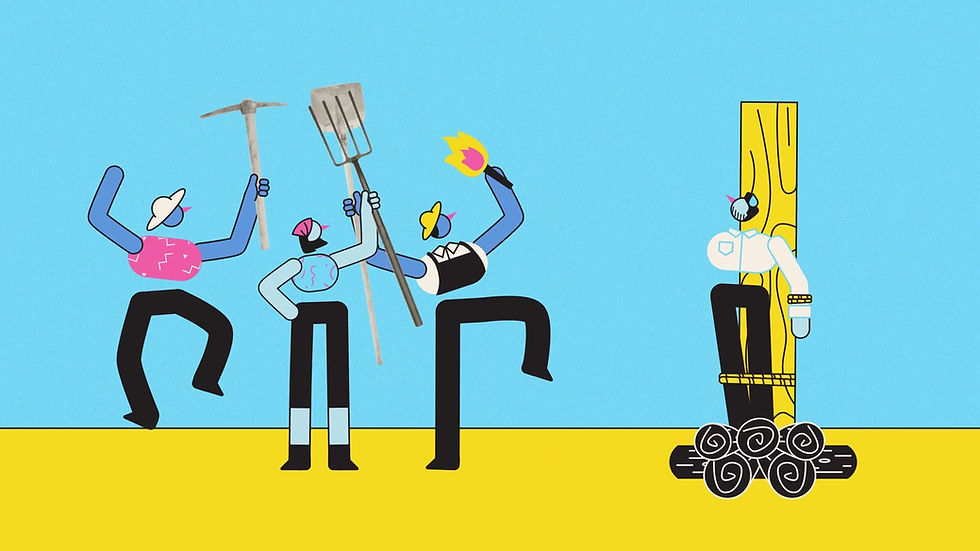

But while viewers revel in the deceit (poor Paloma!), the experience for those playing the game is very different. Because science tells us that lying – especially sustained, face-to-face deception – takes a genuine toll on the mind and body. Behind every slick bluff and perfectly timed accusation, there’s an invisible psychological cost.

Let’s unpack what research reveals about the strain of sustained lying, and why even the most seasoned celebrity may find The Traitors more draining than a week on I’m a Celebrity.

Lying is hard work

Contrary to the myth of the smooth liar, deception usually demands far more mental effort than telling the truth. You must suppress the honest response, invent an alternative, keep your story straight, track who knows what, and manage your expression and tone. That mental juggling act ramps up what psychologists call cognitive load – the strain of balancing too many thoughts at once.

That might explain why Jonathan Ross – despite the slick appearance of a callous mob boss attending a rainy “funeral” in sunglasses and fur coat – had less than glowing words to say about his experience, claiming he found the “constant lying really wearing” and “increasingly uncomfortable.” Ross later took to X to clarify:

I am pleased I did it - an extraordinary experience - but I did not enjoy the duplicity as the game progressed. It’s a tougher psychological challenge than I expected is all.

A 2024 fMRI study reframed deception not as a simple on–off switch in the brain, but as a series of shifting states, which would go some way to explaining why The Traitors is not all fun and games. When participants lied, their brains didn’t just light up in one area; they moved through distinct neural modes – some inclined toward honesty, others calibrated for deceit. Remarkably, researchers could predict with nearly 90 per cent accuracy whether someone was lying based on which “brain state” they were in.

A second 2024 study went further, teasing apart what’s truly “lying” from what’s just decision-making or self-interest. The same brain regions that spark during deception also activate when we chase rewards or dodge punishment – both familiar motivators inside The Traitors’ castle. So part of the “lie signal” may simply be the brain’s reward circuitry firing as players juggle ambition, fear, and guilt in real time.

Taken together, these findings suggest that deception isn’t a single, fixed behaviour but a dynamic interplay between emotion, memory, and motivation. Lying is both a mental workout and an emotional balancing act, which might explain why, on The Traitors, even the most composed contestants look exhausted long before the final round table.

A Slippery Slope

But some traitors are naturals, right? Take Harry Clark – the Series 2 winner who so effortlessly pulled the wool over fellow contestant Mollie’s eyes that you’d think twice before trusting his Sunday roast compliments ever again. And then there’s Minah Shannon from Series 3 – visibly crestfallen at the mere thought of not committing a murder.

But here’s the twist: the human brain can adapt to dishonesty. What starts as a nerve-shredding test of conscience can, with repetition, become surprisingly easy. Neuroscientists at University College London found that the amygdala – the almond-shaped region of the brain that processes fear and guilt – fires intensely the first time we lie, but quiets with every repetition.

That dampening effect has a behavioural consequence. As the emotional discomfort fades, people tend to tell bigger and bolder lies – a “slippery slope” of dishonesty. It’s not that the moral boundaries disappear; it’s that the physiological resistance to crossing them weakens. For contestants on The Traitors, that means the first quiet whisper of betrayal might send the heart racing, but after a few successful manipulations, the deceit feels routine. Their brains have recalibrated.

This neurological adaptation isn’t unique to reality television; it’s the same mechanism that underlies desensitisation in everyday moral decisions. White lies told for convenience or to keep the peace train the brain to tolerate deception, especially when those lies are rewarded – with money, approval, or, in this case, survival. Over time, the amygdala’s moral “sting” fades, making dishonesty not just easier, but almost automatic.

Yet while the mind may grow numb to guilt, the body keeps score. Psychophysiological studies show that deception triggers the body’s stress systems – elevated heart rate, spikes in electrodermal activity (tiny changes in sweat gland response), and even dilated pupils. None of these signals can definitively “prove” a lie, but they reflect just how hard the body is working to keep the story straight.

The Hidden Cost of Secrets

If the physiological toll of lying is visible – the fidgeting, the fatigue – the psychological cost is quieter but no less damaging. Research led by psychologist Michael Slepian at Columbia University shows that the real weight of a secret isn’t in keeping it hidden:

The problem with having a secret is not concealment… It’s that you have to think about it, you have to live with it. Even when you don’t have to hide it, it can hurt you.

That persistent rumination, he says, can affect a person’s well-being – mood, relationships, performance – and can lead to social isolation if people feel they’re not being authentic with those around them.

Interesting, then, that more than one “faithful” has described feeling isolated during their time on the show. Like Kas, from Series 3, who found himself targeted not for anything he’d done on the show (save raising a toast at breakfast), but for his day job as a doctor. Fellow contestant Jake suggested it “made sense” for him to be a traitor, favouring the narrative that Kas was “saving lives during the day and killing faithfuls at night.” The comment, framed as logic, left Kas feeling ostracised and unable to reconnect with the group. By the fourth episode, he was banished.

There’s a lot to be said for the damaging effect of false accusations. Even though The Traitors is “just a game,” the brain doesn’t necessarily distinguish between strategic deception and moral breach. The physiological and emotional costs can feel strikingly real.

There’s also the social fallout. Humans are hardwired for reciprocity – to trust and be trusted – and betrayal disrupts that circuit. To play the game, traitors must weaponise intimacy: forming alliances, feigning loyalty, then orchestrating elimination. Over time, that kind of deception starts to wear you down.

Still, not everyone pays the same price. Studies in cognitive psychology suggest that preparation, compartmentalisation, and self-awareness can buffer the effects of deceit. Players who frame lying as part of a temporary role (“this is performance, not identity”) experience less amygdala conflict and recover faster after the stress ends. And you only need to watch Alan Carr cackling in the turret over murdering his BFF to know that he’ll be perfectly equipped to leave the paranoia where it belongs – on screen.

Comments